3360 words

Of Worldometers’ list of the world’s countries by GDP, 64% of the lower quartile are in Africa.1 52 out of 54 countries in Africa have been colonised by European powers; with the worst offenders being Britain and France, followed by Spain, Portugal and Belgium.2 This is not a coincidence, not even mere correlation, this is causation.

Preface – A Note On African History

The African continent is home to approximately 1,490,000,000 people3 – or 17.89% of the total world population – currently, not to mention the origins of Homo Sapiens, aka human life.

Despite this, African history is drastically understudied in the West. In England, following the national history curriculum (last updated in 2013) students are not mandated to study any African history in Key Stages 1-3, safe for “a non-European society that provides contrasts with British history” where one option includes “Benin (West Africa) c.AD 900-1300.”4 Following this, students in Key Stage 4 typically move to studying GCSEs, where they may opt to study history; before progressing to A-Levels in Key Stage 5. Here, unfortunately, diversity does not improve. The following data is from the major exam boards AQA, Edexcel and OCR; and summarised in the book ‘Why Study History?’:

74.7% of GCSE modules and 79% of A-Level modules cover Europe and the British Isles.5 Global and non-Western history comprise just 7% of A-Level and 11% of GCSE papers. Asia and the Middle East are seldom studied outside of a global imperial context. Africa and South America are entirely absent from the curriculum except when studied in broader topics in relation to empire, the slave trade, exploration, or international relations.6 Furthermore, as of 2016 only two British universities required history students to study Asia-only modules, and none featured core modules that focused exclusively on Africa, South America or Oceania.7

Essentially, African history is either omitted or centred on events such as a slave trade, which claimed the lives of more than 15 million men, women and children across four centuries8, or empire; neither of which do justice to the rich history of the African Continent, and are often too forgiving to the cruelties of European colonisation.

This is, without a doubt, highly dangerous. Ignorance, especially historical ignorance, is a gateway to prejudice and discrimination.The lack of education for young people on the history of Africa can easily lead to misunderstandings such as mistaking Africa for a sole country, disregard for the slave trade, lack of awareness for the mass-colonisation of Africa and its consequences (the focus of this essay) as well as omitting celebration for the continent’s liberation and de-colonisation process. Not to mention, this does not just lead to white British children being uneducated on diverse histories, but fails the growing BAME student population (~27.6% of the 2022 GCSE cohort9) by denying access to representation, and the history of their cultures, which are no less important than British ones.

I felt as though it would have been disingenuous to write this without acknowledgment to the lack of African representation in British history education, and want to conclude this preface by recommending the book ‘It’s a Continent’ by Astrid Madimba and Chinny Ukata. It’s incredibly well researched, and anecdotally recounts a historical event for each African country (outside of the slave trade and colonization process..) which importantly distinguishing each country’s national identity – I’d like to note that especially, as I’m conscious that this essay often employs generalisations of Africa as a whole, despite the continent’s diversity.

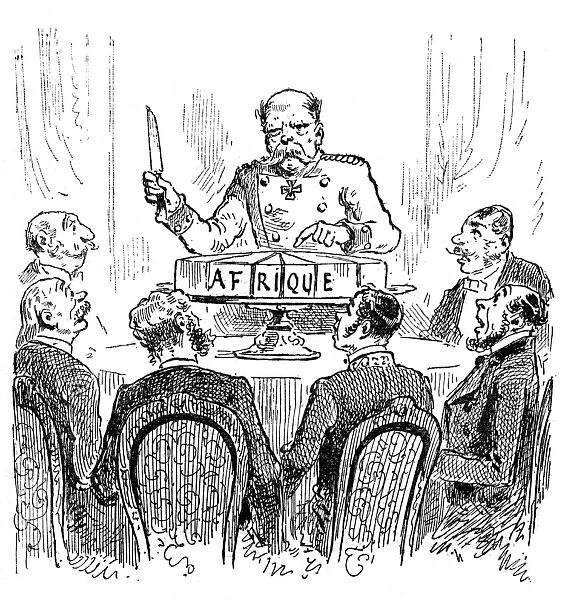

The ‘Scramble For Africa’ of 1881-1914 is the most prominent period of African colonisation, but do note that it was not the beginning, as the Portuguese had “marked the beginning of the integration of [Southern Africa] into the new world economy and the dominance of Europeans over the indigenous inhabitants”10 in the 15th century.

A key event in understanding this period is the Berlin Conference of 1884 – if you’ve ever looked at a map of Africa and wondered why the borderlines are so arbitrarily straight, this may be the answer that you are looking for. Not only were no Africans invited to the conference, “there were still large swathes of Africa on which no European had ever set foot”11 which meant that the borders were drawn up with complete disregard to pre-existing communities. Historian Olyaemi Akinwumi (of Nasarawa State University in Nigeria), interprets the event as the crux for future inner African conflicts:

“The foundation for present day crises in Africa was actually laid by the 1884-85 Berlin Conference. The partition was done without any consideration for the history of the society … The conference did irreparable damage to the continent. Some countries are still suffering from it to this day … People had learnt to live with borders that often only existed on paper. Borders are important when interpreting Africa’s geopolitical landscape, but for people on the ground they have little meaning.”12

One of the main factors that drove the subsequent Scramble for Africa was economic prospects, and aims to exploit Africa’s natural resources. Colonialism was, as noted by a UNESCO report, “constructed on the control of natural resources, [and] created new forms of inequality and exacerbated existing ones.”13 The paper explains, “the desire of European powers to capture and exploit African resources played a key role in the transformative process of colonialism. The core characteristic of the colonial project was the alienation of natural resources … [colonialism caused and exacerbated] inequalities which have endured into the present day. Colonialism was about controlling natural resources, and many of the inequalities on the continent today are reflected in unequal access to the continent’s natural resources.”14

I’m no economist, but all it takes is a quick google search to identify that international trade is fundamental to economic growth; and Africa has only about 2 percent of all world trade.15 Thus, it is not necessarily surprising that the continent has the “highest extreme poverty rates globally … Africa’s extreme poverty rate was recently estimated to be about 35.5%, 6.8 times higher than the average for the rest of the world.”16

What does appear conflicting, though, is that Africa is home to approximately 30% of the world’s mineral reserves, as well as 40% of the world’s gold and up to 90% of its chromium and platinum. The largest reserves of cobalt, diamonds, platinum and uranium in the world are in Africa, alongside 65% of the world’s cultivable land and 10% of the planet’s renewable fresh water source.17

So why are Africa’s resources so rich, while the continent largely remains poor?

Firstly, a report from the UN Environmental Programme finds that “Africa loses an estimated USD 195 billion annually of its natural capital through illicit financial flows, illegal mining, illegal logging, the illegal trade in wildlife, unregulated fishing and environmental degradation and loss”18 – natural capital which accounts for between 30-50% of total wealth (varying by country).

Another key reason for Africa’s poor economy is the lack of developed infrastructure. An article from the National Bureau of Economic Research states that “For the two major determinants of human capital, education and health, Africa fares poorly.”19 Indeed, if the African rates of primary school enrollment in the 1960s (a decade of note, but more on that later) had been closer to Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) levels, it’s estimated that the continent’s average economic growth rate of 0.9% would have been a much healthier 2.37%, and incomes today would be 2.5 times larger than they actually are; similarly, life expectancy in the 1960s was 27 years younger than OECD levels, if this had not been the case then Africa’s annual growth rate would have been 2.07% larger; and outbreaks of malaria since the 1960s has harmed the economy to the tune of an estimated 1.25%.20 The article also notes that military conflicts, many of which were sown by colonist forces, have been a factor in hindering Africa’s economic growth.

Further evidence confounds this interpretation that the country’s infrastructure is lagging behind, with data from the Centre for Global Development finding that:

“In 2022, 600 million people – half of Africa’s population – still lacked access to electricity and 418 million people had no access to clean drinking water. While roads are critical for the transport of passengers and goods, only 43% of Africa’s rural population has access to an all-season road and just 53% of roads on the continent are paved. In terms of railway network, with an estimated density of 2.5 kilometre per 1000 square kilometres, Africa lies way below the global average (23 kilometre per 1000 square kilometres).”21

It is not a stretch to assign these issues of infrastructure to the fall-out of colonialism.

A paper by Joshua Settles explains that pre-colonisation, “African economies were advancing in every area, particularly trade. The aim of colonialism is to exploit the physical, human, and economic resources of an area to benefit the colonising nation … The development of colonialism and the partition of Africa by the European colonial powers arrested the natural development of the African economic system.”22 Essentially, contrary to European myth, Africa was not ‘uncivilised’ prior to colonisation, rather the continent was in a stage of development that colonisation actually stunted for Western gain.

A further way to determine how colonisation impacted African infrastructure and economy is to deal not in plausible counterfactuals – which do convincingly suggest the “contrary” to the argument that “there is any country today in Sub-Saharan Africa that is more developed because it was colonised by Europeans”23 – but in analysing the situation in Africa during the de-colonisation period of the 1960s (I told you the decade was significant!)

Dubbed the ‘Year of Africa’, 1960 was a turning point for the continent, with 17 countries declaring independence and welcoming in a wave of de-colonisation. Notably, there were a number of successful independence movements prior to 1960, with two of the most significant being South Africa (1910) and Egypt (1922)The reasons these countries are so noteworthy are, firstly, it was another two decades until another African nation gained independence, and that these countries which experienced colonisation for the least amount of time hold the silver and bronze medal for richest African country (with Nigeria clinching gold).24 Conversely, the newest African nation is South Sudan, which declared its independence from the Republic of the Sudan in July 2011, and is reportedly the poorest country in the world.25 Coincidence? I think not.

The 1960s, as noted above, were a critical time for many African nations, with standards of education and healthcare much lower to global counterparts, largely due to the hitherto colonisation. Explained succinctly by Settles,

“The policies of colonialism forced the demise of African industry and created a reliance on imported goods from Europe. Had native industry been encouraged and cultivated by the coloni[s]ing powers, Africa would probably be in a much better economic and technological position today.”26

When colonising forces withdrew from Africa, they tended to take any semblance of infrastructure or aid with them. In some cases, namely the Comoros Islands, the subsequent economic havoc and decline in living standards led to some Africans wishing to be recolonised (this request was made to, and declined by, the French in 1997.27) Leander Heldring describes similar consequences in post-colonial Uganda, stating, “these societies [where there was no significant pre-colonial state formation] were very ready to adopt better technology when it appeared, and any gains that there might have been in terms of stability were reversed when the British left in 1962, bequeathing to the Ugandans a polity with no workable social contract resulting in 50 years of political instability, military dictatorships and civil war.”28

I should note, none of this is an argument for colonisation, rather acknowledging that a nation being recognised as decolonised and autonomous doesn’t erase the long lasting consequences of imperialist intervention – as has been seen, and as the following study of Ethiopia will reiterate, the European expansion into Africa was purely selfish in nature; any claim that colonisation was to ‘civilise’ Africa or grow economies (which obviously couldn’t have been achieved without assistance from the supposedly ‘superior’ West) is baseless, and arguably racist, propaganda.

Ethiopia has a history of considerable interest, as it’s often regarded as one of just two African countries (alongside Liberia) that were never colonised; though this is sometimes contested for both. In Ethiopia’s case, this absence of colonisation was not for European, specifically Italian, lack of trying – as described by Britannica:

“Ethiopia is one of the world’s oldest countries, its territorial extent having varied over the millennia of its existence …The present territory was consolidated during the 19th and 20th centuries as European powers encroached into Ethiopia’s historical domain. Ethiopia became prominent in modern world affairs first in 1896, when it defeated colonial Italy in the Battle of Adwa, and again in 1935–36, when it was invaded and occupied by fascist Italy. Liberation during World War II by the Allied powers set the stage for Ethiopia to play a more prominent role in world affairs. Ethiopia was among the first independent nations to sign the Charter of the United Nations, and it gave moral and material support to the decolonisation of Africa.”29

It’s these years, following Emperor Menelik II’s victory over Italian occupational forces, that I’d like to centre on, for, as described by Astrid Madimba and Chinny Ukata, they “came to represent what an African nation could achieve without European interference.”30 Menelik is heralded as one of Ethiopia’s greatest rulers, and it is not hard to see why – having fended off the Europeans in the late 19th century, Menelik focused on the country’s development. His investments were centred on the education system: he built schools and encouraged students to study abroad to broaden their horizons and, in turn, the nation’s long-term development. Additionally, he made investments in healthcare by creating hospitals, and improved transport infrastructure by building railroads, improving roads, and developing telecommunications.31 His rule is testament to what Africa could have been without colonist intervention, and Menelik’s legacy is preserved in the fact that Ethiopia remains the continent’s fifth richest country.32

The unfortunate truth of history is that Ethiopia is largely an anomaly; and the vast majority of African nations suffered through colonisation, only for their independent statehoods to not yield significantly higher prospects. Western historians (myself guiltily included) are oft-entranced by the dictatorships of Germany and Russia, yet oblivious to the multitude of autocracies that have risen and fallen in Africa, especially following formal decolonisation. A 2004 paper found, “there have only been 189 country-years of democracy in Africa compared to 1823 country-years of dictatorship between 1946 and 2000. Moreover, dictatorships still outstrip the number of democracies in Africa by a considerable margin despite the transitions to democracy that occurred in the early 1990s.”33 Two decades on, 22 dictatorships remain in Africa.34

Clearly, then, there is a link between the withdrawal of colonial force and establishment of dictatorship in Africa, but why? One reason is the curated archetype of the ‘benevolent dictator’, seeking (whether genuinely intentioned or not) to rescue their country following the destruction by Europe. A key example of this is Malawian autocrat Hastings Banda (in power 1963-94), who was initially seen as a saviour – the ngwasi, or Black Messiah; but eventually instituted policies that deteriorated freedom of press and normalised execution of opposition.35

Moreover, Mathieu Kérékou of Benin rose to power in a coup against French occupation forces in 1972 (which were present despite the country being declared independent in 1960). Kérékou is an interesting antithesis to Banda, and an example of how African leaders are just as multifaceted as those in the West, though are often not given this credit, and objectively deemed good or bad. Now celebrated as the ‘father of Beninise democracy’36, Kérékou initially led a one-party Marxist state which he described as “our own [Beninese] social and cultural system”37 – a typical dictator move of inciting nationalism to garner support. Madimba and Ukata describe how,

“Kerékou’s government was no exception [to consequences of one-party state rule], with human rights abuses reflected in executing and imprisoning opponents … Although Kérékou’s administration initially brought public service reforms, his presidency became associated with mismanagement and incompetence … the threat of imprisonment and extra-judicial killings … Many courageous workers, students and intellectuals ended up either dead or tortured by Kérékou’s government.”38

However, eventually in 1991, Mathieu Kérékou made history as the first former dictator on the mainland continent to admit defeat in an election; with many identifying that his change of heart and reformation from autocracy was likely a result of “the poor state of Benin’s economy at the end of the 1980s [and] because of a change in global politics as the Cold War came to an end.”39 Unfortunately, dictatorship has since returned to Benin in the form of businessman stroke politician Patrice Talon, who became President in 2016, and “adopted an arsenal of strategies from corruption to state violence”40 to maintain power.

Nowadays, as Benin highlights, the situation has not improved. Polling has indicated that the reason for this is largely that many Africans have lost faith in (admittedly apparently flimsy) democracy: the proportion of those who prefer democracy to any other form of government has dropped by 9% in the past decade, and a majority of 53% said a coup would be legitimate if civilian leaders abuse their power. In South Africa, 72% say that if a non-elected leader could cut crime and boost housing and jobs, they would be willing to bypass democratic elections.41

Robust scientific analysis proves that, more often than not, autocratic leadership hinders economic growth: “growth-positive autocrats (autocrats whose countries experience larger-than-average growth) are found only as frequently as would be predicted by chance. In contrast, growth-negative autocrats are found significantly more frequently … growth under supposedly growth-positive autocrats does not significantly differ from previous reali[s]ations of growth, suggesting that even the infrequent growth-positive autocrats largely ‘ride the wave’ of previous success … [the] results cast serious doubt on the benevolent autocrat hypothesis.”42

Therefore, it is valid to identify the rise of dictatorship and despotism in many parts of Africa as a consequential replacement of colonialism, which has further served to exacerbate Africa’s general poverty and economic challenges by inhibiting growth.

All of this brings me back to this essay’s titular notion of how, as a result of European colonisation, many African countries have been trapped into a seemingly inescapable categorisation as a ‘developing country’. Evidence strongly corroborates this interpretation – in the UN’s 2024 iteration of ‘World Economic Situation and Perspectives’, for instance, all African nations were denoted ‘Developing economies’, and 33 of the 46 ‘Least developed countries’ were situated in Africa.43

Madimba and Ukata’s book makes a similar assessment of Africa’s stagnant economy; they also report the phenomenon as nothing new, and identify the link to (de-)colonialism:

“Economists and historians have described the 1980s as Africa’s ‘lost decade’, or the ‘locust years’, as newly independent states struggled to find their feet after years of colonialism, failing to develop at the same pace as the rest of the world. During this time, many African countries fell behind in living standards, education, and healthcare access, with income per capita declining. In a sense, colonisation’s legacy developed the rest of the Western world in terms of raw material for European industrialisation at the detriment of African countries’ development – leaving many in a permanent state of identifying as ‘developing’ nations.”44

This history cannot be erased, but it needs to be acknowledged, so that its effects can be reversed. As has been discussed, colonialism has led to poor infrastructure, meaning that Africa has disproportionately worse healthcare facilities, leading to increased prevalence of disease, e.g. relentless outbreaks of AIDs45; poorer education availability, leading to high rates of illiteracy46; and a greater rate of dictatorship than any other continent.

In other words, the legacy of European involvement in Africa – most detrimentally from the ‘Scramble for Africa’ period – is shameful and long lasting; and perhaps even the most significant reason into why such a resource-rich continent is experiencing such extreme poverty and economic ruin, condemning 54 countries into the trapping category of ‘developing’.

- Worldometer, ‘GDP by Country’ (WorldoMeters 25 July 2023) <https://www.worldometers.info/gdp/gdp-by-country/>. ↩︎

- Alistair Boddy-Evans, ‘A Timeline of African Countries’ Independence’ (ThoughtCo 2019) <https://www.thoughtco.com/chronological-list-of-african-independence-4070467>. ↩︎

- Worldometers, ‘Population of Africa (2023) – Worldometer’ (www.worldometers.info) <https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/africa-population/#:~:text=Africa%20Population%20(LIVE)&text=The%20current%20population%20of%20Africa>. ↩︎

- Department of Education, ‘National Curriculum in England: History Programmes of Study’ (GOV.UK 11 September 2013) <https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-history-programmes-of-study/national-curriculum-in-england-history-programmes-of-study>. ↩︎

- Marcus Collins, Why Study History?. (London Publishing Partner 2020). ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- United Nations, ‘Slave Trade’ (United Nations 2015) <https://www.un.org/en/observances/decade-people-african-descent/slave-trade>. ↩︎

- Department for Education, ‘GCSE Results (Attainment 8)’ (www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk17 October 2023) <https://www.ethnicity-facts-figures.service.gov.uk/education-skills-and-training/11-to-16-years-old/gcse-results-attainment-8-for-children-aged-14-to-16-key-stage-4/latest/#by-ethnicity>. ↩︎

- Shula Marks, ‘Southern Africa – European and African Interaction from the 15th through the 18th Century | Britannica’, Encyclopædia Britannica (2020) <https://www.britannica.com/place/Southern-Africa/European-and-African-interaction-from-the-15th-through-the-18th-century>. ↩︎

- Hilke Fischer, ‘130 Years Ago: Carving up Africa in Berlin | DW | 25.02.2015’ (DW.COM 2015) <https://www.dw.com/en/130-years-ago-carving-up-africa-in-berlin/a-18278894>. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- James Murombedzi, ‘Inequality and Natural Resources in Africa Sustainable Development Goals United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’ (2016) <https://en.unesco.org/inclusivepolicylab/sites/default/files/analytics/document/2019/4/wssr_2016_chap_09.pdf>. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Florizelle Liser, ‘“Trade Is Key to Africa’s Economic Growth”’ (United States Trade Representative 2022) <https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/blog/trade-key-africa%E2%80%99s-economic-growth#:~:text=Right%20now%2C%20Africa%20has%20about>. ↩︎

- Debbie Woods, ‘Poverty in Africa’ (Outreach International 26 September 2023) <https://outreach-international.org/blog/poverty-in-africa/#:~:text=Africa%20has%20the%20highest%20extreme>. ↩︎

- UN Environment, ‘Our Work in Africa’ (UNEP – UN Environment Programme 25 October 2017) <https://www.unep.org/regions/africa/our-work-africa#:~:text=The%20largest%20reserves%20of%20cobalt>. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Les Picker, ‘The Economic Decline in Africa’ (NBER January 2004) <https://www.nber.org/digest/jan04/economic-decline-africa>. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Samuel Pleeck and Mikaela Gavas, ‘Bottlenecks in Africa’s Infrastructure Financing and How to Overcome Them’ (Center For Global Development 11 December 2023) <https://www.cgdev.org/blog/bottlenecks-africas-infrastructure-financing-and-how-overcome-them#:~:text=Crucial%20infrastructure%20needs%20in%20Africa&text=Sub%2DSaharan%20Africa%20still%20lags> ↩︎

- Joshua Settles, ‘The Impact of Colonialism on African Economic Development the Impact of Colonialism on African Economic Development’ (1996) <https://trace.tennessee.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1182&context=utk_chanhonoproj#:~:text=The%20infrastructure%20that%20was%20developed>. ↩︎

- Leander Heldring and James Robinson, ‘Colonialism and Development in Africa’ (CEPR 10 January 2013) <https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/colonialism-and-development-africa>. ↩︎

- Worldometer, ‘GDP by Country’ (WorldoMeters 25 July 2023) <https://www.worldometers.info/gdp/gdp-by-country/>. ↩︎

- Luca Ventura, ‘Poorest Countries in the World 2024’ (Global Finance Magazine 1 May 2024) <https://gfmag.com/data/economic-data/poorest-country-in-the-world/#:~:text=Current%20International%20Dollars%3A%20455%20%7C%20View>. ↩︎

- Joshua Settles, ‘The Impact of Colonialism on African Economic Development the Impact of Colonialism on African Economic Development’ (1996) ↩︎

- Astrid Madimba and Chinny Ukata, It’s a Continent (Coronet 2022). ↩︎

- Leander Heldring and James Robinson, ‘Colonialism and Development in Africa’ (CEPR 10 January 2013) <https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/colonialism-and-development-africa>. ↩︎

- Assefa Mehretu and Donald Edward Crummey, ‘Ethiopia | History, Capital, Map, Population, & Facts’, Encyclopædia Britannica (2019) <https://www.britannica.com/place/Ethiopia>. ↩︎

- Astrid Madimba and Chinny Ukata, It’s a Continent (Coronet 2022). ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Worldometer, ‘GDP by Country’ (WorldoMeters 25 July 2023) <https://www.worldometers.info/gdp/gdp-by-country/>. ↩︎

- Matt Golder, Leonard Wantchekon and Mrg217, ‘Africa: Dictatorial and Democratic Electoral Systems since 1946 *’ (2004) <https://www.princeton.edu/~lwantche/Africa_Dictatorial_and_Democratic_Electoral_Systems_Since_1946#:~:text=The%20coding%20results%20in%2047> ↩︎

- World Population Review, ‘Dictatorship Countries 2020’ (worldpopulationreview.com 2021) <https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/dictatorship-countries>. ↩︎

- Astrid Madimba and Chinny Ukata, It’s a Continent (Coronet 2022). ↩︎

- BBC News, ‘Benin’s “Father of Democracy” Mathieu Kerekou Dies at 82’ BBC News (15 October 2015) <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-34537057> ↩︎

- Astrid Madimba and Chinny Ukata, It’s a Continent (Coronet 2022). ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- BBC News, ‘Benin’s “Father of Democracy” Mathieu Kerekou Dies at 82’ BBC News (15 October 2015) <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-34537057> ↩︎

- Astrid Madimba and Chinny Ukata, It’s a Continent (Coronet 2022). ↩︎

- The Economist, ‘Why Africans Are Losing Faith in Democracy’ (The Economist 5 October 2023) <https://www.economist.com/leaders/2023/10/05/why-africans-are-losing-faith-in-democracy>. ↩︎

- Stephanie M Rizio and Ahmed Skali, ‘How Often Do Dictators Have Positive Economic Effects? Global Evidence, 1858–2010’ (2019) 31 The Leadership Quarterly. ↩︎

- United Nations, ‘World Economic Situation and Prospects 2024 | Department of Economic and Social Affairs’ (www.un.org 4 January 2024) <https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/world-economic-situation-and-prospects-2024/>. ↩︎

- Astrid Madimba and Chinny Ukata, It’s a Continent (Coronet 2022). ↩︎

- World Health Organization, ‘HIV/AIDS’ (WHO | Regional Office for Africa25 February 2024) <https://www.afro.who.int/health-topics/hivaids#:~:text=There%20are%2025.6%20million%20people%20living%20with%20HIV%20in%20the%20African%20region.&text=In%202022%2C%20about%20380%2C000%20people>. ↩︎

- UNESCO, ‘Education for All Global Monitoring Report: The Hidden Crisis: Armed Conflict and Education; Gender Overview’ (Unesco.org2011) <https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000212003>. ↩︎

Leave a Reply